By Dr Jyotsna Jha

Director: Skills COL

Governments in developing countries rarely undertake detailed economic costing exercises for public service delivery, and policy choices are often made without this information. Costing exercises are generally limited to financial plans where costing norms for a particular service, say a new course based on an open learning philosophy, are often decided based on some basic requirements and financial considerations without paying adequate attention to aspects of rights and quality assurance. Towards the end of May (27-31 May 2024), COL is organising an international event for participants to work on the costing of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes using blended learning approaches. This will be held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in collaboration with two premier local institutions and with the participation of premier TVET institutions from Jamaica, Kenya, Nigeria, Sri Lanka and Zambia. Here, we will consider the context of the need for such interventions that help cost an education service following a comprehensive framework.[i]

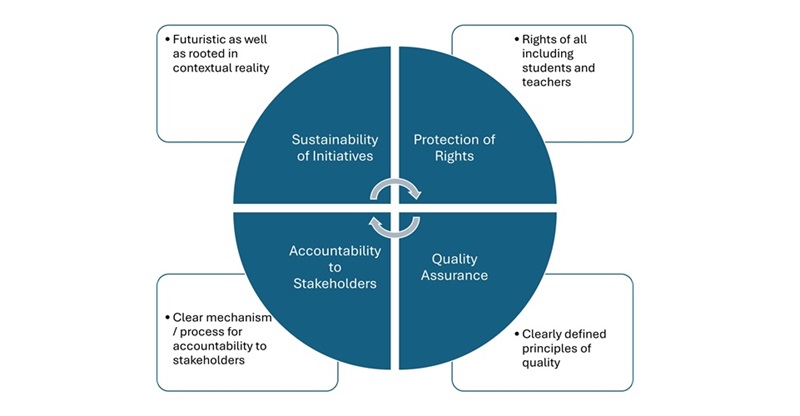

The main arguments are that (i) it is important to estimate the costs of service delivery because this helps in public policy decision-making in the areas of budgets, subsidies, and cost recovery, and (ii) the costs need to be estimated by considering the economic costs of providing a high-quality service while unpacking the dimensions of quality and defining the rights of all concerned.

The exercise has implications for developing facilitative costing principles and guidelines as well as the size of the public budgets meant for respective services. It is not necessary that the concerned government pay for the entire cost through its budgetary allocations. Resource generation through diverse sources, including public contribution and private partnership, is possible, and a comprehensive costing exercise helps in predicting the resource requirement and apportioning it to the contributions, which otherwise mostly remain unacknowledged. It is also possible to introduce cost-saving measures and change the cost estimates using such frameworks if the rights and quality parameters are not compromised. The parameters themselves can be flexible as long as they are based on principles that are clearly defined and commonly understood.

Rights here refer to the rights of all concerned, including future students and teachers. For instance, adherence to these parameters would mean adhering to existing legal frameworks for estimating teachers’ remuneration in respective countries or following the norms of what is considered desirable in terms of facilities for developing open resources. These need to be based firmly on analysing diverse national and local practices, and therefore, the costing guidelines being discussed in the workshop in Malaysia are based on case studies conducted for the premier institutions with national mandates in four out of six participating countries.

In addition to rights and quality, the other two pillars of this framework are accountability and sustainability. Both of these also need to be rooted in local practices, but, as in the case of the other two, universal principles also come to play a significant role. Accountability, for instance, can be linked to the practice of having a feedback loop from users or a system of reporting to key stakeholders. Sustainability, on the other hand, needs to be rooted in integrating the use of local resources, knowledge and thresholds on various contours while also being futuristic and cognizant of global practices and trends. For instance, costing of any new blended-learning-based TVET programme needs to take note of the internet penetration and affordability in a country into account while also being aware of the fact that hybrid learning and credentials-based learning are going to become more common in future, and therefore any such investment may not be untimely. This could imply that costing needs to take future needs also into account.

This costing framework, therefore, could look like the diagram above.

While considering the framework, the actual costing exercise needs to document all the components and processes in detail, taking their nature (capital or recurrent) and periodicity into account. Every single activity remains important, and therefore, analyses of diverse case studies play a very important role, as they provide a range of experiences and contexts that could feed into guidelines that can be made generally applicable. That is what the purpose of the Malaysian workshop is.

This blog is intended to introduce this concept for discussions in the context of the forthcoming workshop, but the framework is applicable to other aspects of education and most other public services and, therefore, open for a wider discussion.

[1] Reference: Jha, Purohit and Pandey, 2020; Journal of the British Academy, 8(s2), 7–39, https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/008s2.007), which can be accessed at JBA-8s2-02-Jha-Purohit-Pandey.pdf (https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/)